UPDATE: As of September 27, the WGA strike is over after 148 days. As of November 9, the SAG-AFTRA strike is over after 118 days.

The ongoing labor disputes in Hollywood have led to groundbreaking strikes taking place in the past few months, which have unnerved future filmmakers and screenwriters at WS.

On May 2, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) declared the beginning of their strike due to failed negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). Through the negotiations, the WGA attempted to create a new, fair contract between the two parties, through proposals including changes to residual payments and terms around the use of artificial intelligence (AI). After a very similar process, the Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA) also declared their strike on July 14.

“Here’s the simple truth: We’re up against a system where those in charge of multibillion-dollar media conglomerates are rewarded for exploiting workers,” reads the introduction of SAG-AFTRA’s “Why We Strike” page.

The coinciding of these two strikes is a historic event; the last time a “double strike” occurred in Hollywood was in 1960. The WGA’s strike, the longer of the two, lasted 148 days. The present-day WGA strike has surpassed 100 days so far.

“The first step that comes with creating a film, a TV show, or a video game, is a script. Even if it’s not in the most traditional form, there has to be some sort of story laid out before you can go anywhere,” said senior Adam Martineau, an aspiring filmmaker. “It’s already hard enough to get your foot in the door, and you have to kick even harder to be able to live in the industry after already making it.”

Issues surrounding fair payment to writers and actors were one of the main catalysts for the strikes. In 1960, the pay structure for residuals was developed, which are long-term payments writers and actors received every time a show had a rerun or was purchased as a DVD. After the advent of streaming, however, these payments have decreased dramatically.

“[Writers and actors] more than deserve to have better pay. They always have, but especially during these days of streaming that create an entirely different playing field,” said senior Alex Sigurdson, an aspiring screenwriter. “The strike is a way for writers to get better pay, but also to bring them closer to the top, alongside executives.”

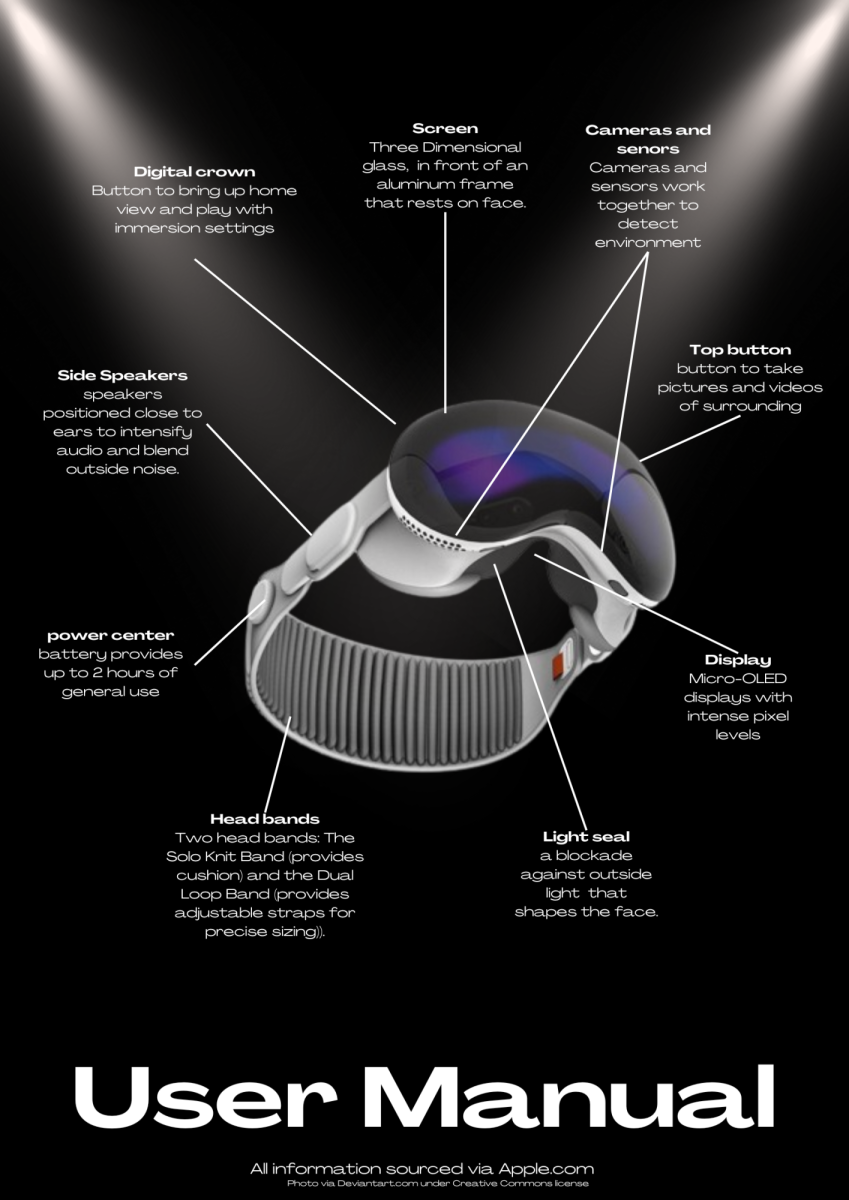

Alongside pay issues, the use of AI, its uncertainty, and danger of replacing workers was a key matter in both strikes. Creating terms around its use was an important part of negotiations.

“Storytelling is an inherently human thing, so I don’t think AI can necessarily tell stories as well as we can. At the same time, these production companies and these CEOs are trying to find a way around paying writers and actors fairly,” said senior Mia Chetelat, a prospective screenwriter with the goal of creating a production company highlighting marginalized groups in film. “I think that’s why we see the rise in wanting to use AI, because [production companies] can cut out the middleman and still be making money.”

The instabilities being addressed by the strikes are an important part of the argument, and a key reason that many students who are aspiring filmmakers or screenwriters are feeling discouraged about entering the industry.

“A lot of people who like art don’t go into art because their future is not stable. Normally, writing is one of the more stable creative opportunities, but it’s not stable anymore because companies are utilizing AI and aren’t paying their people a livable wage,” said senior MJ Denny, an aspiring screenwriter. “It’s becoming almost as nuanced and difficult as art has always been, [though] it is a form of art.”

A common stereotype for people who decide to pursue a career in the arts is the “starving artist” trope, which perpetuates the notion that people who pursue these careers must sacrifice their well-being and stability. Alongside other stereotypes and general ignorance, this is why artists have not commonly been afforded much respect, and among the reasons writers and actors are having to fight so hard to have their needs met.

“Writers are frequently credited with the short end of the stick, a sort of ‘why would they ever write that?’ when something odd happens in a film. Sometimes it really is a case of bad writing, but it’s more often due to heavy time constraints or the fact that it’s common practice for studios to hire a writer to write one or two episodes, fire them, then hire a new one. It’s cheaper than keeping one writer throughout the whole show,” said Sigurdson.

The AMPTP has been mostly silent on negotiations, letting union members’ needs continue to be unmet.

“The endgame is to allow things to drag on until union members start losing their apartments and losing their houses,” said an anonymous studio executive in a Deadline article.

Given that this statement is from an anonymous source, and the AMPTP publicly stating they and other anonymous sources were not speaking on behalf of the association, this plan will not necessarily be put into motion by the AMPTP. By the time negotiations do start happening again, predicted outcomes are uncertain, but students looking to enter the industry are optimistic.

“Hopefully, should the writers and actors win this, my career will be more financially stable,” said Sigurdson. “At the very least, I’ll worry a little less about having a ‘day job’ while I try to write scripts on the side.”

Martineau’s analysis of the situation described a decision between two paths that most aspiring high school filmmakers must make. He explained that a student usually either goes to film school and makes connections in the industry from there, making some films along the way, or instead takes the money they would have put toward school and make an independent film, trying to build their career from there. He hopes that the strikes being resolved will make the decision easier.

“For me, it’s definitely a hard thing to think about because if it continues to stay this way, when I finally want to enter that world, I’m going to have to find a way to work around it,” said Chetelat. “But that’s the good thing about people who write, people who act—artists—is that we will find a way around it eventually.”