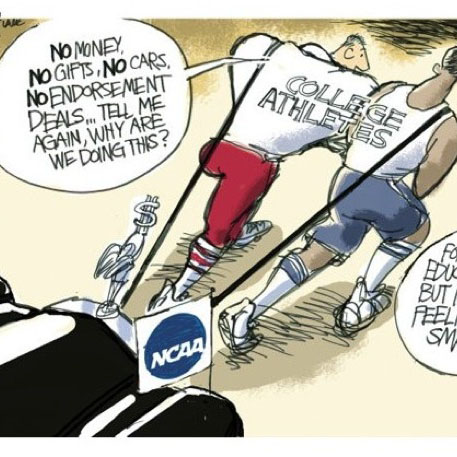

Are athletic scholarships enough?

Photo courtesy of Eagle Cartoons

February 19, 2016

From the football fields to the basketball courts, college athletes represent their university through their effort and athletic ability in an attempt to earn their school prestige, recognition, and of course, revenue.

However, no matter how much cash the school rakes in because of their efforts, the athletes see none of it.

High school is viewed as a four-year period in which youth prepare to enter the real world. To the majority of these youth, college is viewed as the next step in their preparation.

According to The New York Times, 65.9 percent of high school graduates enroll in college. Of these graduates, many are high school athletes looking for scholarships. And not all of these athletes are lucky enough to get their college paid for.

Earning an athletic scholarship is no small measure. Athletes often dedicate their youth and young adult lives to the task of mastering one or more sports.

This dedication carries on into their college endeavors, where they spend on average 40 hours each week practicing sports. Student athletes give up many other oppurtunities in high school and through college if given the opputrunity to play competitively with optimistic goals for the future.

In terms of workloads, college students average 15 hours in class and 30 hours studying each week. Add in sleep, a job or two, and college students have just over 15 hours a week of free time, or just under two hours a day.

“There is very little time to fit a job [into] an already limited [and] stressful student athletic schedule,” said senior Aidan Pastel, who just recently committed to Georgia Tech.

Many argue that the time and dedication put forth by these athletes for their respective universities is enough merit for a pay check from their academy, just as if they were an employee of the school.

In terms of hours spent training with their team and by themselves, the workload is similar to that of a full-time professor. Even more so, college students have less than a ten percent chance of going pro, emphasizing that the majority of this work and effort goes toward the school, and rarely towards the athletes themselves.

“[College life and athletics will be] much harder. It’s a whole new level of athletes, [and it will be] difficult until I get my schedule down,” said senior Maura D’Anna, who will be playing basketball at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

The other side of the issue argues that paying athletes is not the solution.

The NCAA claims that colleges do not have the budget to pay their students, which is partly true. Colleges are non-profit organizations, which mean excess revenue is spent, and they have no profit remaining. Hypothetically,

In order to pay for player salaries, universities would have to adjust their budget to incorporate athlete payment, which could be practically impossible for some schools because the amount athletes would receive could not fit into the budget.

Like college athletes, college students have a large workload.

Many of these students also participate in other activities, such as band and theater, which take up large portions of their day as well.

The argument is that if college athletes are paid, so should other students participating in school-sponsored organizations.

A few potential alternatives to paying athletes are increasing short-term scholarship bonuses allowing the athletes to earn sponsorship deals independent of the school.

Both have their limits, but the bottom line is that college athletes feel that they do not see a fair share of benefits for their efforts.

“Financial aids, like scholarships, are incredibly helpful [and] allows athletes who may be incredibly gifted at their sport but are in tough financial situations to compete,” said Pastel.