Stop assuming students trust their counselors

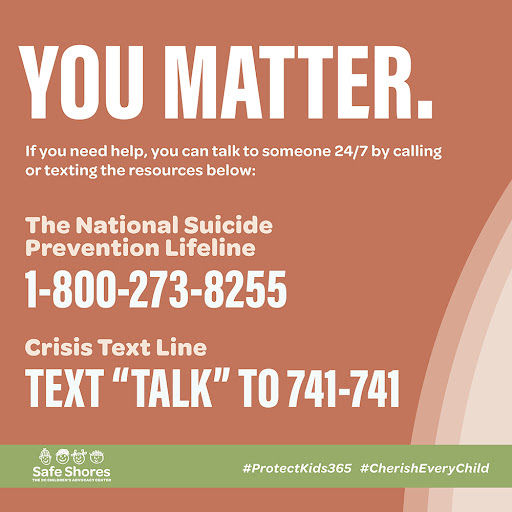

Photo courtesy of safeshores.org under Creative Commons License

If you or a friend is experiencing suicidal thoughts, actions, or symptoms of depression, help is available. Call The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or text the Crisis Text Line for 24/7 anonymous help from trained volunteers.

May 26, 2022

Having a trusted adult whom a student can go to for help is extremely important, but trust has to be earned, and just because someone holds the title of counselor, parent, teacher, or administrator does not automatically mean they can be trusted.

In April, juniors were given a Signs of Suicide wellness lesson and screener by MindWise Innovations during their advisory classes. Although meant to help, many students found this lesson to be a jarring and triggering approach to addressing mental health with minimal warning.

This is not to say the lesson should not have been taught. According to a study conducted in Fairfax County at the end of 2019, nearly 30 percent of 11th and 12th grade students had experienced symptoms of depression, 14.3 percent of all survey takers had considered suicide, and six percent had attempted suicide in 2019, so it is clear why the lesson was deemed important. However, in a recent Oracle conducted survey taken by juniors, over 60 percent said the Signs of Suicide MindWise Innovation lesson taught during LS/4 should have been taught differently.

As for the screener that students had to fill out after the lesson, nearly 40 percent of juniors who participated in The Oracle’s survey reported they untruthfully answered no to questions on the screener, and over 80 percent were scared they would be reported or pulled out of class to talk to their counselor if they honestly answered the screening questions.

Students are afraid of being forced to talk to their school counselor about their mental health because they don’t trust them. If the administration wants students to talk to trusted adults, they can’t force trusted adults on them, nor can they only show interest in their students’ mental health on a select one or two days during the year.

The lesson juniors were given encouraged them to ACT: acknowledge, care, and tell. While acknowledging and caring can be simple, telling an adult isn’t as easy. Especially if students feel like the adult they are talking to doesn’t care about them or the person they are reporting as much as they do, or if they will immediately tell their parents, which again, are not automatically trusted adults.

In order to effectively ensure strong and safe mental health among the student body, the focus needs to be on training teachers, counselors, and faculty year-round to reach out and build stronger relationships with their students so they can find trusted adults to talk to on their own. Having students sit through a presentation that, according to 50 percent of survey takers, did not accurately depict depression and suicidal thoughts, as well as fill out a mandatory form that forced them to open up about sensitive topics to adults they don’t trust or know, only makes students more afraid to willingly seek help.

Teachers and other staff need to reach out to students, make it known they are there for them, treat them like human beings with emotions every day of the year, and build a connection that makes them worthy of being trusted. Students will be less afraid of getting help for themselves or their friends if they actually trust the adults they are told to talk to and know those adults genuinely want to help them.

With all this being said, if Signs of Suicide by MindWise Innovations saves even one student, it’s worth it. However, when it comes to teaching depression and suicide prevention, switching the focus from forcing students to talk to counselors they may not trust to having teachers and counselors make rapport-building connections with their students could save many more lives.