WS from the 1800s to now

Photo courtesy of Brian Henitz

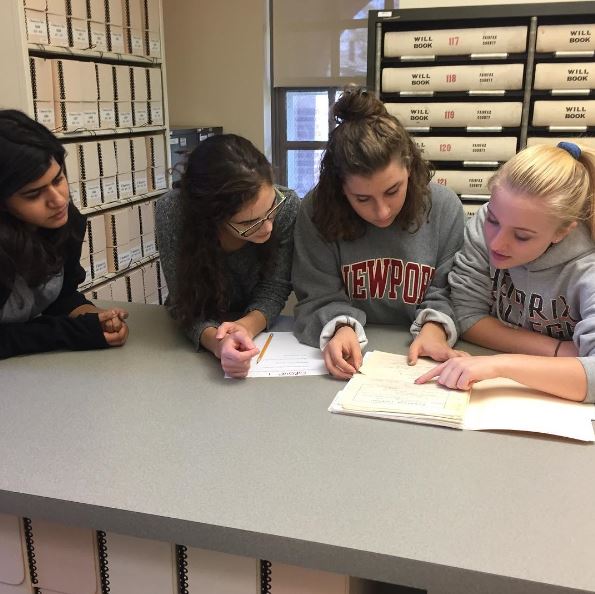

Applied History students dig through the pages of historical documents at the Fairfax Circuit Court Records Center

December 15, 2016

Hypothesis: WS has no history.

Data: Not many students believe that WS has anything of note. We are not named after a president or a general. We are not home to many famous alumni. We are not built on a battlefield. The only history it seems like we’ve made are the national news stories of food fights and dance teams.

“I have no idea what the history of this school is other than the fact that half of the math department graduated from here,” said senior Larissa Pawlowski.

To be fair, the seniors were born in the late 1990s, and with the school having been in use since 1967, the student body has missed a lot of history. Even still, perhaps the most exciting history would be knowing that the Annandale Atoms, the Robinson Rams, the Lake Braddock Bruins, and the West Springfield Spartans got their mascots because of an alliteration trend in the ‘60s.

Since last spring, history teacher Brian Heintz has been researching WS’s past, becoming familiar with the story of not only the property but of some of the various individuals involved since the 1800s.

“You find adults appreciate history a lot more than young people because after a certain time of perspective, you kind of realize those connecting things that make it meaningful to you,” said Heintz. “Now, more and more, through the process of discovering this, I found it to, in a way, tell the history of this country just as effectively as George Washington or George Mason or anybody else.”

The West Springfield area originally got its name from a 19th century land developer named Henry Daingerfield, who christened his development Springfield Station. The nearby railroad depot adopted the name, making it official. In the post-World War 2 era, the expansion of suburbs led to them developing their own communities with designated names. Daingerfield’s Springfield mostly encompassed the area near Backlick Road, thus making us West Springfield.

“We knew that [WS’s] property split where the school is itself, between an Ulam and a Charlotte Barker. Prior to [the Barkers], it would’ve been partially part of the Ravensworth plantation, with the rest belonging to William Barker, and his house is actually where Hidden Pond is,” said Heintz.

The majority of the research was conducted by last year’s Applied History students interning with Jeff Clarke, who makes videos on how schools in FCPS developed their names. While Heintz supplemented their research, it was left largely up to the students, who ultimately wrote the video’s script. Instead, he focused more on the individual, Ulam Barker, and has since branched off to investigate connecting elements of history to achieve a wider perspective. In Heintz’s effort to uncover the full history of the West Springfield area, he has also used it as a teaching point for his Applied History class on how to conduct offline research.

“We [went] to the archives room and we looked up a lot of the ways that they keep the documentation. We [completed] a paper where we filled out what we found about Ulam Barker and his will and everything. That was really cool—looking at his will and where he allocated everything,” said senior Deborah Schaelling, one of Heintz’s Applied History students.

Heintz has been teaching for 22 years, and oftentimes students will suggest that he get a Ph.D. He, however, has no intention of doing so. While writing a book on Thomas Jefferson to be placed among all the others that have been published is very low on his to-do list, developing his research on local, relatively unknown subjects remains a point of interest for him.