Marking a lost history

Photo courtesy of Madison Bell

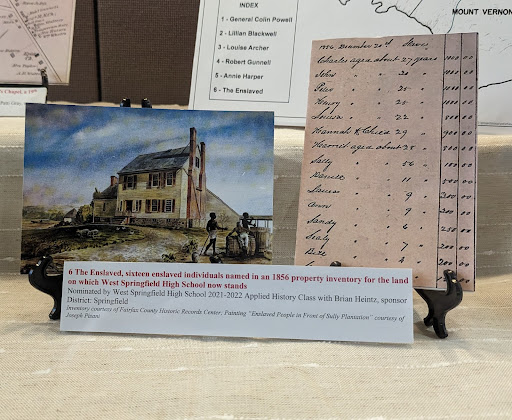

The marker will feature the names of Charles (27), John (20), Peter (25), Henry (25), Hannah (29) & Child, Louisa (22), Harriet (38), Daniel (11), Ann (9), Laura (9), Sandy (6), Sealy (Celia, 7), Bill (4), Cora (4), and Sally (56).

WS is participating in a county-wide initiative highlighting African-American history by establishing a historical marker honoring the 16 enslaved people who lived on school grounds.

The Applied History class, led by teacher Brian Heintz, submitted their suggested topic to the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors in 2022. Their suggestion, alongside five others, was recognized in a February meeting with the board, but the research into the lives of the 16 enslaved people on WS school grounds extends back to 2015.

In preparation for the school’s 50th anniversary, the Applied History class took part in a video project called “What’s in a Name?” which covered the origins of school names in the county. Students in the class began an internship with the producer of the program, Jeff Clark.

“Mr. Clark is a producer but is also the de-facto historian of FCPS. He worked with Applied History student interns in the Spring of 2015 in researching the school’s property history. That was when we came across the December, 1856 will and estate inventory (list of property and values, so that an estate can be divided according to the will), and there it was: human beings listed like property along with the blacksmith tools, horses, and cabbages,” said Heintz.

At the time, local historians were aware of WS’s history as a part of the former plantation, Ravensworth, and later another smaller farm. However, the names of the 16 enslaved people who occupied it in the late 19th century went relatively unnoticed. Those included in the estate inventory were not given last names but were assigned monetary values.

“It was both a shocking and exhilarating find. Too easily, we relegate the past to disconnected terms and events. This happened here on the very ground we stand,” stated Heintz.

The class brought their findings to the school, which were added to the Local History section of its website. The class then began to design a memorial for school grounds, but was not able to come to a complete consensus on what it should look like. It was not until 2022, when the Historical Marker Project was announced, that a marker could be constructed to physically recognize the lives of the enslaved population.

“When I found out last year that Fairfax County was having a competition for African American Historical Markers, it was an easy choice to send a submission. I shared the sources and the topic and that was enough for it to be one of the winners. Compared to the other winners, I feel it represents the best in terms of original research, rather than identifying figures whose names were already known,” said Heintz.

The marker will utilize the same color scheme and a similar design to those already placed throughout the county; however, there were some changes that needed to be made.

“We have worked it out with the company [that designs the markers], Sewah Studios, to include a chart of the enslaved [people], their ages, and their monetary values. This will be a first for the company. We felt that the chart format would have more impact visually than a long list,” stated former Fairfax County History Commission member and historian Mary Lipsey.

The Historical Marker Project is meant to expand students’ knowledge about local history and share stories of African-Americans that were overlooked in the past, but the task of uncovering this history comes with some unique challenges.

“The difficulty of the project is that there are no textbooks that include our county’s African American history,” said Lipsey in an interview with the Connection Newspaper.

The lives of African-Americans are still underrepresented in history. The monolithic nature of how students are taught the narratives of enslaved people and the lack of proper documentation makes it difficult to research individual lives. Yet even the small step of creating a marker allows for the recognition of 16 people who have been denied it for over 168 years.