The hypocrisy of book banning in FCPS libraries

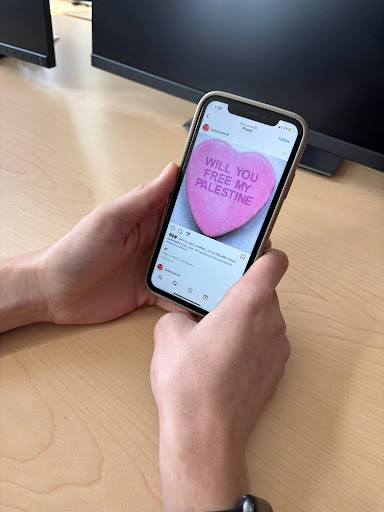

Photo courtesy of Saharla Mohamoud

According to Lee and Low Books, diversity has gone up in publishing in recent years, with bookshelves seeing 3% more POC and 7% more LGBTQIA authors in 2019 since 2015. Despite the inclusivity within modern literature, authors are still just as susceptible to censorship in talking about their own experiences than they were in the past.

Fairfax County Public Schools has made the decision to reinstate the books Lawn Boy by Jonathan Evison and Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe following backlash due to their sexual content and alleged pedophilia. The school board has agreed that the books maintain FCPS’s commitment towards providing students diverse LGBTQIA+ content and contain no pedophilia.

The texts were removed from library shelves and reviewed by two committees of students, teachers, and staff in order to determine whether they are appropriate for a school environment after a school board meeting where parents expressed their converns over the nature of the books.

Still, the reinstatement caused an uproar during the most recent school board meeting when numerous parents voiced their discontent with FCPS upholding ‘pornography’ in school libraries and sparked protests outside the meeting in an appeal to get school board members fired.

Gender Queer is an illustrated memoir and Lawn Boy is a coming of age novel, both of which explore gender and sexuality through the lives of the narrators. The books do contain sexual material and Lawn Boy, the book accused of containing pedophillia, has a scene where an adult man reflects on a sexual experience he had when he was in the 4th grade with another 4th grader. Gender Queer and Lawn Boy have both been acclaimed in the past for providing students useful information about queer identities, helping LGBTQIA+ students find a text they can seek comfort in.

Parents have made the appeal that their reasoning for banning these books isn’t based on the LGBTQIA+ content, yet only one of four books in that meeting contained heterosexual content. The only thing certain is these appeals to protect high school students only hinder them from understanding real-world topics.

Book banning is anything but foreign to American history. The Comstock Act of 1873 made sending or possessing publications deemed “obscene” or “immoral” illegal. Due to its vague nature, the act caused numerous court cases and sparked a debate on what is truly considered lewd content, allowing the works of renewed writers like Oscar Wilde, an LGBTQ figure, and Ezra Heywood, an early feminist, to fall under scrutiny.

Book banning is still happening today, and the same types of books keep making the lists — books that discuss racial issues, and like Gender Queer and Lawn Boy, books that discuss LGBTQ+ issues. In 2019 alone, eight of the books in the American Library Association (ALA) top ten most challenged books list contained LGBTQIA+ content, and in 2020, six of the ten most challenged books discussed race.

When books containing heterosexual mature content like Looking for Alaska by John Green and Atonement by Ian McEwan are allowed to be in the library and taught within our schools, the true reason why parents are fighting to keep Lawn Boy and Gender Queer off the shelves becomes even more transparent.

And sure, the experiences shared in the two novels may be sexually explicit, making it uncomfortable for parents to allow their students to consume, especially with Gender Queer’s highly illustrated presentation. Cases like this, however, are where parental responsibility comes in. At the end of the day, media consumption is not the responsibility of school librarians; it’s right in the hands of the student and their guardian. FCPS librarians do not need to remove books from their shelves because one parent doesn’t want their kid exposed to certain types of material.

The only job of the school library is to provide information and resources for students to connect with the real world and experiences both in and outside their own. Being exposed to controversial and expansive work from authors of all types of backgrounds does just that. It’s not like sex, a basic biological function, and sexuality, a common aspect of human existence, are nonexistent outside of school environments.

A good and valuable piece of literature forces its readers to look within themselves and learn about perspectives and viewpoints they wouldn’t otherwise have access to. Censorship in school libraries, especially of marginalized groups, does just the opposite.

Of course, there’s the fundamental belief that a school library is meant to ensure safety, but there is no safety in hiding novels that reflect the world students are living in. Do recognize, there’s truly nothing wrong with literature that forces the reader to challenge their own preconceived notions, especially if those preconceived notions start to harm other parents, teachers, and most importantly, students.