It’s time to rethink your period-tracking app

Photo courtesy of Jensen Kugler

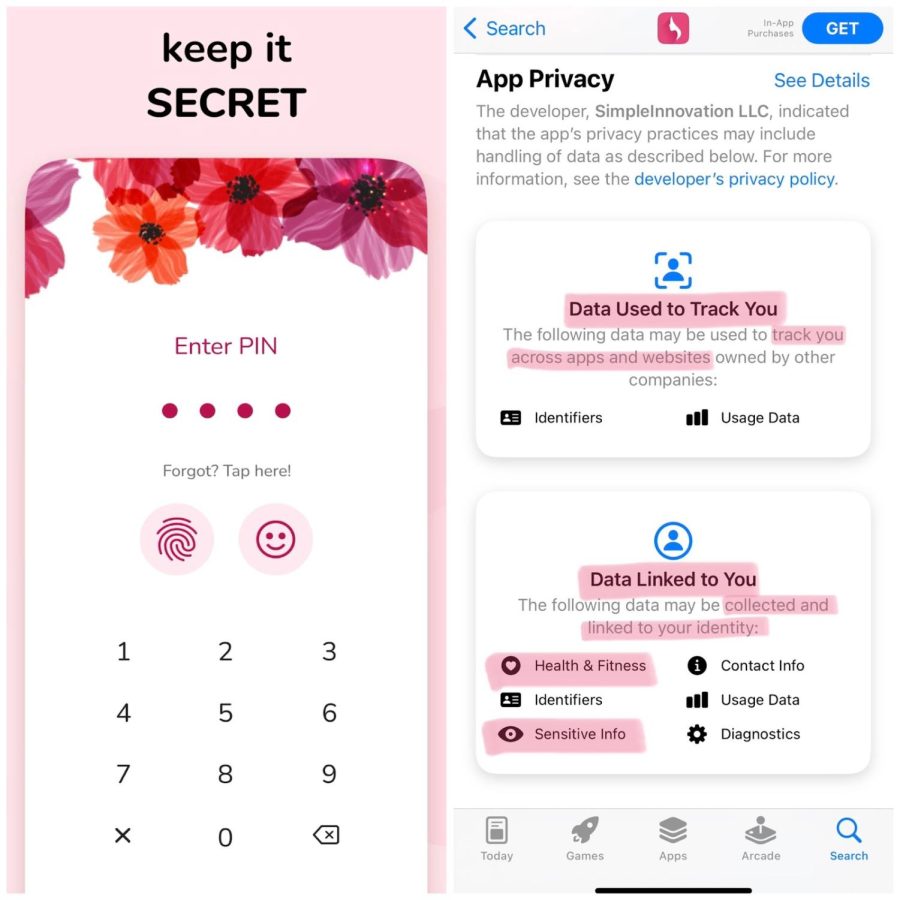

In the App Store, My Calendar is advertised as secure because it has pin, Thumb ID, and Face ID options. Despite these additional safety features, the app tracks and links personal data as seen in the App Privacy section. This demonstrates how important it is to be mindful of terms and conditions, particularly for something as personal and sensitive as menstrual data.

Virginia Senate Bill No. 852, which would have prohibited the issuance of search warrants for menstrual health data, passed in the state Senate before stalling in the House. While the bill did not pass, it raised important questions about the safety of period-tracking apps in a post-Roe world.

Search warrants grant law enforcement the authority to explore places, things, and people for the purposes of an investigation. As of now, there are no restrictions on what information can be requested using a search warrant, so police can legally request menstrual data if they deem the information relevant to a case. Despite the legality, Fairfax County Police Department Detective Bryan Huntley was hard-pressed to come up with a situation in which menstrual data would be necessary for a case.

“I have not used any kind of search warrant for that purpose,” said Huntley. “It’s a 99.9% percent chance [that menstrual data will never be needed for an investigation].”

The bill was advertised by its Democratic sponsor Senator Barbara Favola as a protection of personal privacy. Its proposal reflects trends in lawmaking towards both increased online privacy and increased protections for menstruators after the overturning of Roe v. Wade. That said, cell phone privacy is already a concern in regard to criminal investigations. Any app that collects data, regardless of the reason, can be accessed by third parties.

“I do write a lot of search warrants for cell phone data,” said Huntley.

Currently, abortion is legal in Virginia up until the end of the second trimester, or nearly seven months. If abortion were to become a criminal offense in Virginia, Senators like Favola worry that menstrual data from period-tracking apps could be used against their constituents.

“I think we all have a reason to be very wary of the information we’re putting out there,” said government teacher Brian Taylor. “We live in an increasingly complex society, and that really does allow people to be exploited.”

Perhaps no one at WS will ever have to worry about the safety of their menstrual data, but in a nation where laws that impact reproductive rights are so frequently changing, everyone should be aware of the possibilities.

“You don’t know how [data collected from you] is going to be used,” said Taylor. “I can’t even conceive of all the ways it could be used, so [the] bottom line is try to keep what’s private, private.”

Of 50 menstruators polled, 67% said they use period-tracking apps.

“I use this app called My Calendar; it autosaves all the stuff I input, whether it’s how I’m feeling or where I am on my cycle,” said senior April Carter. “I [looked] through all the [apps] that seemed like they had less [of a chance] or [need] to charge me for something.”

Convenience tends to be a priority for choosing apps, and period trackers are no different.

“I use Flo because I’ve been using it forever, and it’s pretty accurate most of the time,” said senior Neena Kirlew.

But choosing an app because it is the first result, or because it is free, is not always wise in terms of security. The safety of period-tracking apps is complicated, unsurprisingly. Of course, the easiest way to avoid the possibility of personal period data being used in a search warrant or subpoena is to simply not use an app. Those who do, however, should keep a few things in mind.

In order to keep app data safe, cell data must be kept secure. Two-factor authentication, Face ID, and complex passwords are all wise. Always read the app description, reviews, and terms of service. Look for apps that have privacy settings in place, and avoid apps that claim to collect information for any reason. If the app has an anonymous setting, it is a good idea to use it.

The choice to use or not use a period-tracking app is entirely personal, but be aware of the risk. Take a look at the app again and make sure it is the best option.