COVID’s impact on the oil market

Photo courtesy of Renerpho via Wikimedia Commons under Creative Commons License

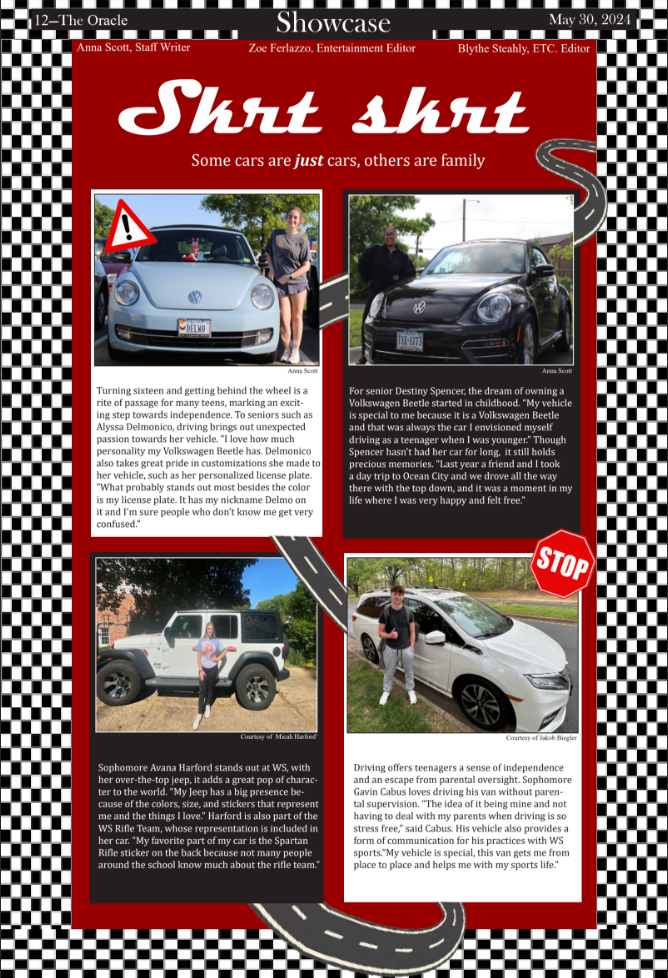

WTI Futures on April 20, 2020.

May 15, 2020

If you told Americans during one of several oil embargoes in the 1970’s, or the invasion of Kuwait during the Gulf War, that oil prices would plummet below zero in 2020, they would have laughed at you. On April 20th, during the height of the coronavirus lockdown, U.S. oil futures did just that.

Oil is traded on the stock market as futures:buyers bid on price per barrel to be delivered at the future date specified in the contract. Normally, the quick movement of the supply chain and the consumer purchases of gasoline means that constant oil production is necessary, and oil storage usually remains pretty open. A sharp decrease in demand due to lockdown orders across the world is causing this storage to fill fast.

On April 20th, demand had decreased so sharply that the May oil future prices for West Texas Intermediate, the U.S. oil price standard, went negative. As their futures contracts turned into a liability, oil traders were forced to pay buyers up to $37.50 per barrel in order to deliver their contracts.

In response to the 30% reduction in global demand, the member countries of OPEC agreed to slow production, starting May 1st, by about 20 million barrels a day, an unprecedented halt to over 15% of the total global oil output. Some analysts say this supply reduction will likely not be enough, and some predict global demand could decrease by up to 30% as shutdowns persist.

After another plunge on April 27th, traders and policymakers are looking for a way to stabilize the market as U.S. companies sharply reduce their production, and some, like Whiting Petroleum and Chesapeake Energy, descend toward bankruptcy. At the current pace, U.S. oil stores will likely be at capacity by mid May.

Firms are implementing a variety of measures to limit the damage to the oil market, including debt restructuring, alternate storage methods and production cuts. Ultimately, the market will continue to suffer until reopened economies produce a new demand to refine this unprecedented surplus of oil.